the typical story

I think everybody who wants to publish a book has the same thought at first. You’re going to write a book, you’re going to send it out to one of the big publishers with their super recognizable names, and you’re going to hope that somebody notices you, little ole new you, in between publishing the tenth book by one of their big named authors.

“publishers provided most support for the bestselling authors, taking fewer risks on authors that had not yet proved their profitability” (Martire 85)

It’s a one-in-a-million chance. Or at least that’s what everybody who tries to discourage you from pursuing your dream tells you. Because writers don’t make money.

‘‘I feel like the press is more of a hobby in that I don’t see it making money, whereas at the start I thought it would. Long term I don’t think I’ll ever make a living out of publishing and that’s been a surprise’’ (Bold 98)

introducing small and micro presses

Recently, but not so recently (let’s say about two to five years ago), I started to get bugged by the idea of small and micro press publishing. Not as a complete concept but I started seeing Etsy and Patreon zines being spread around by people I followed online. It was cute, it was cool, it felt personal.

Me: “Why can’t I do that?”

The thought came, planted itself in my head, and started to grow deep within my brain. I’d print off my own “completed” works to keep personal copies for myself. I kept putting off actually trying to bind the prints because Word is a dingus at formatting anything but now I have access to InDesign so I cannot and will not be stopped.

“This idea of publishing as a hobby, an ‘‘accidental profession’’, instead of a business is one that characterises a couple of the publishers interviewed for this research” (Bold 98)

That’s still somewhere within the realm of self-publishing though. And it was just to have something of mine to keep for myself. Sometime within the last year though, between getting more serious as a writer and realizing that it’s putting your work out there that matters, I’ve been thinking about other ways to, at the risk of repeating myself, put my work out there.

Does a book have to go through these traditional channels in order to be valid?

According to a wide variety of people, the answer is no.

“In an industry sliding inexorably toward monopolies, mainstream publishing’s focus on bestsellers is widely understood to have led “to the limitation of smaller, more diverse voices” ([43], 90), whereas micro- and small presses (MSPs) “love to provide a location for writing that doesn’t or can’t find a voice in the mainstream media” [19], 48).” (Martire 213)

Poinciana Paper Press

When Poinciana Paper Press opened its door I was in the middle of my query into whether we have to let dreams die to achieve the stability you never really had. Stability that was still always going to be “one dad day” away from unstable. No matter how far away you go from the starting point, that’s always the truth.

“As we have seen, small presses are often the easiest routes into traditional publishing for emerging authors, especially for those without literary agents. Many internationally successful authors started their careers with small publishers. However, these authors inevitably leave to publish bigger companies that can offer larger advances and marketing budgets” (Bold 92)

Here I was, experiencing what was possibly the youngest-ever middle-age crisis, and there comes a Press. Not even half an hour from my house (it’s actually two with high traffic).

With the landscape of The Bahamas, it feels like an impossibility to imagine a world where you’re a writer, author, creator, etc. We’re surrounded by some of the best writers in the world. Where are their major releases? Their based-on-the-novel-esque movie? Their three book deals? If you even do writing, it’s on-the-side or something you do-in-your-free-time.

“The consolidation of the book publishing industry has resulted in an increased focus on bestselling authors: ergo, it is more difficult for new and emerging, or nonmainstream, authors to get published” (Bold 99)

The appearance of the press seemed to feed the spark that had been growing for the past few years. Why couldn’t I do these things myself? What if there are other people also doing things themselves? The other questions would be who, why, what do they get out of it, if small presses publish small authors or if small authors submit to small presses what is the effect?

“Independent publishers, especially the smaller presses, are often run for the love of the product rather than for profit, and their output is guided by taste rather than consumer insight and sales data” (Bold 99)

The answer to the first is Sonia Farmer, founder of Poinciana Paper Press and the others might be answered in the following interview.

Interview with Sonia Farmer

What inspired you to join the publishing field?

I'm going to answer this by combining it with the question below:

Why did you choose to start your own printing press? Why not join an established company?

In 2007, I developed an interest in the publishing world. At that time, I was earning my BFA in Writing at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn NY and working through the discomfort of a strange internship experience with a small literary agency. Sifting through slush piles to find a “marketable” chick lit submission to pitch to my boss week after week had worn me down. I realized that this money-driven publishing model didn’t have a place for me— it was too heartbreaking, as a writer, to exist in a space where literature became secondary to profit.

“Unless writers and editors are independently making decisions about what writing is published and how it’ s talked about, they are subject to profit/loss models and decisions driven by capital” (Plum 16)

Two electives that I took the following semester would help me locate my place in publishing: “The Art of the Book” with Miriam Schaer, and “The Tiny Presses Shall Inherit the Earth” with Ryan Murphy. With Miriam, I learned how to make books by hand and realized that books could be part of the storytelling experience, that I could control every aspect of my narrative as writer and maker.

“process was “a much more intimate experience than any of the [previous presses]. … And I felt that [the publisher] really cared about the manuscript in a way that I hadn’t had before” (Martire 222)

In Ryan’s class, I joined other writers who, like me, had felt out of place in the publishing field. We explored the world of small press publishing, mostly through local small presses like Ugly Duckling Presse, Spectacular Books, and Belladonna*. Publishers would visit the class and share the stories of starting their presses or literary magazines and showcase their chapbooks. In their stories I heard myself—all of them were writers who started presses to build platforms for themselves and other writers in their community who could not find an outlet for their work due to marginalization, unmarketability, or experimental writing forms that could not be categorized in a bookstore. In their books I saw the handmade aesthetic I was learning about in my book arts class—pamphlets bound with needle and thread; author names and titles debossed on covers through letterpress printing; vibrant illustrations through relief printing; handmade and decorative papers. Yes, this felt right. This is how books should feel. This is how books should function.

“Small publishers are perhaps most well known for working in distinct literary niches, what Bourdieu [4] called the field of restrictive production, such as poetry, experimental fiction, regional writing, or new and emerging genres, which are not mainstream and thus often neglected by larger publishers” (Bold 92)

I decided to establish my own press to make books in this way, collaborating with Caribbean writers and artists. I could not see, at that time, many regional prosses making books in this way, so I did what I saw the publishing guests in our classes do: make up a name, and make some books, and then just keep making books.

“One of the main problems with becoming a writer in the West Coast…there was very little in the way of a West Coast publishing scene…so it was pretty evident to me that if I wanted to have any freedom to publish the kind of writing about this region then I would have to tackle the problem of how to get it published, and the most obvious thing seemed to be to start my own company” (Bold 91)

Why did you choose to open Poinciana Paper Press in The Bahamas? Also, did the location influence the name or did the name come first?

Ok so back to that Tiny Presses class. For our final project of a limited-edition chapbook I skimmed a short fiction piece, This Is Where Our Feet Could Slip that my classmate Asheley Wilson had submitted to Ubiquitous, Pratt’s literary magazine (where I was editor-in-chief). She was game for this experiment, and even passed along some imagery to go along with the piece. I emailed the Ubiquitous Chief Designer, “Can you show me how to use InDesign?” We met in the student lounge of my dorm between classes for a ten-minute tutorial. Then I was on my own. InDesign was infuriating, but not as infuriating as Microsoft Word, so I stuck with it. I spent a day planning out how to print the inside content consecutively on my home printer. After running out of ink twice, I then broke my printer trying to digitally print the cover image. I used tiny letter stamps for the title and author name on the cover that bled into the paper. Then I bound the dozen or so remaining copies by hand using a three-hole pamphlet stitch that I’d learned in my Art of the Book class. Splitting the copies, Asheley and I were totally thrilled. Making books for my own work in Miriam’s class felt empowering, but making books for other people, I realized then, could be a very rewarding collaborative experience.

“Small presses, such as the publishers interviewed for this research, have less bureaucratic infrastructure than their larger counterparts, and thus have more involvement with the author and title” (Bold 91)

In our last Tiny Presses class, we exchanged the chapbooks. I realized with horror that everyone had made a press name but me. Even after everything I had been exposed to in this class, it hadn’t occurred to me that I could just say and print and press name, and it would be so. I was still, somehow, waiting for permission. But if I was going to keep putting myself through this absolutely gutting and bankrupting and completely rewarding act of making books, I needed a name that unified them, that made them mine—a purpose, a passion, a philosophy. At that time, a name began percolating in my brain, based on the first book I had made in the Art of the Book class using the central image of a Poinciana tree: These trees do not weep. They burn. Poinciana Press, I thought. I had always loved these trees that flowered in a vermillion explosion mid-year for several months across the Caribbean. I wanted my books to have that same arresting presence, and be rooted in the Caribbean landscape.

I volunteered with various small presses in my time living in Brooklyn. There would be “book binding parties” and literary salons and launches in various studios and apartments, and I showed up and learned as much as I could. It was through small press environments that I felt a sense of belonging I hadn’t yet encountered in that foreign space abroad, physically making chapbooks honoring the work of people in this community. I realized through these experiences that small presses are vital hubs for regional literary communities and wanted Poinciana Press to function that way, too—making books, sure, but also functioning as that social, creative, and educational kind of space where exciting friendships, projects, and collaborations are born. I felt we had a vacuum in our literary community for this kind of space. What would happen if I filled it? Could my press function in this way transplanted in home soil?

“Here’s what I have learned during the past eight years running my own book-store and publishing house: You can start absurdly small and grow slowly” (Sharpe 82)

It became Poinciana Paper Press by late 2009, around the time I would publish through Poinciana Press my first two chapbooks: In a China Shop & Other Poems by prolific Bahamian poet Obediah Michael Smith and The Little Death, a first time publication for Keisha Lynne Ellis. With rich and controversial content, these books made no pretense about paradise. Before the launch in December 2009, I flew into town with all of the printed components of the book and a bag of tools to hold my first binding party. We held it in the same place as the launch would be held shortly thereafter, a community art space in downtown Nassau called The Hub, founded by artist Margot Bethel. Offering curatorial assistance to the space was my close friend Jonathan Murray, who I had approached to host us. Fresh after their time as a Junkanoo shack for the scrappy group Sperit, the space was an explosion of cardboard and glitter, but I dusted off the tables and laid the book components and tools. The writers arrived, some friends, some patrons of the space, and a few strangers who had read about it in the newspaper, and we set about making books. I showed them how to collate, assemble, fold, punch holes, and bind. The writers were particularly thrilled about being able to take part in this process. The atmosphere was vibrant, easygoing, just like the binding parties I had known in New York—strangers and friends alike bonded over this act of making chapbooks, and soon enough we were done. I numbered the books and everyone who contributed took a copy home in thanks. I don’t think I’ll ever have the words to express how happy I felt at this moment.

“As the publishing industry consolidates, making it difficult for medium size enterprises to compete, independently, against the behemoths: perhaps the abundance of small and micro-presses will be responsible for disrupting the status quo” (Bold 97)

In 2011, I embarked on a personal research project to investigate how Bahamians published their work. The primary motivation for this research was to help me think about how my small press, Poinciana Paper Press, could serve the community, especially with its handmade aesthetic. The secondary motivation was curiosity spurned by a specific semi-mortifying event where I had to change my small press name due to its existence already as a press.

“Small presses don’ t have capital of that kind, or the history of having exploited it. They’ re taking chances on authors based on community dialogue, local importance, or an intuitive sense for discovery” (Plum 12)

I had invented Poinciana Press because I never heard of it or imagined it existed. During a cursory search on Google, I found nothing. So I claimed it. This is how small presses were made, it had been communicated to me. Ahead of the launch for In a China Shop & Other Poems and The Little Death, I received a panicked email from Obediah forwarding a response to his shared news of the launch for his forthcoming chapbook. It was from the Bahamian author Cheryl Albury, the author of Perspectives from Inner Windows (1996) informing Obediah that she had already purchased ISBNs and published her book under Poinciana Press. Cue panic attack. I reached out to her immediately and apologized and asked if I could purchase the name and ISBNs from her, but she said she had a plan to publish more through her press. Not willing to part with the regal Poinciana, I added “Paper” to the name, reasoning it was a tribute to the handmade aesthetic of my books. Cheryl was, gratefully, understanding and encouraging of this small disambiguation separating our worlds, sharing that she understood the grip of the tree’s beauty.

Back to the research project. I concluded that Bahamian writers have for decades been self-publishing with small presses—such as Guanima Press, Verse Place Press, Silk Cotton Tree Press, Rosebud Press, and Cerasee Books, for example—and making their own anthologies and literary journals—WomanSpeak: A Journal of Writing and Art by Caribbean Women and tongues of the ocean, for example—as acts of survival from a geographical place where our bodies are constantly threatened with erasure. But what if we made books that moved publishing from the realm of survival into the realm of flourishing—so that they become an empowering, creative, and fulfilling practice that can transform the way we see ourselves and the way our country and world sees us? As writers, I think we have been conditioned to think about publishing as something someone else does for us, or something we do for ourselves, but I’d like to use Poinciana Paper Press to explore how publishing can be done with a community, instead of for a community, something that involves positioning myself within the space, and embracing multiple forms of storytelling to help us own our narratives.

“Small presses are run by writers, and anyone can start one—as long as they can steal a little time from their working lives and get a first publication out to their local readers, which isn’t as hard as it sounds” (Plum 21)

Since then, the mission of my small press has evolved from publishing exclusively handmade and limited-edition books of Caribbean literature to using multiple forms of publishing to advance the diversity of narratives in Caribbean literature through a physical hub/location. At first a nomadic press, I established Poinciana Paper Press as a Center for Writing, Book Arts & Publishing in my home country, The Bahamas, in 2022 to position it as a major collaborator in the literary and visual arts communities in the region.

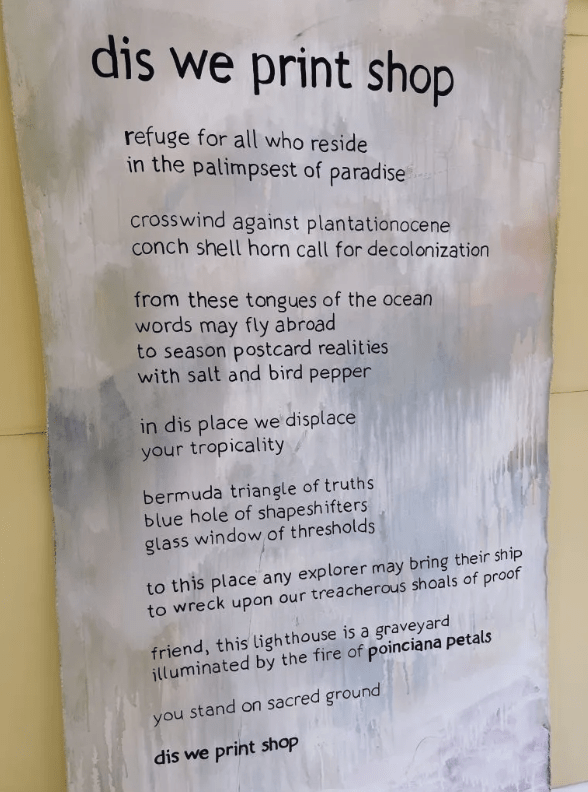

To contribute to a growing and flourishing creative ecosystem in the Caribbean, I’m compelled to physically position my press work within The Bahamas rather than outside of the Caribbean because I think it is vital to our self-determination. I’m particularly excited to align the work I make as a writer and a publisher with a regional pushback against the single Caribbean story and space. Starting with Columbus and enduring to this day through the all-inclusive resorts of the tourism industry, Caribbean identity has been built to sustain and privilege the voice of the visitor as protagonist in places occupied by other bodies and silenced stories. I positioned my creative practice in direct opposition to this privileging. As a writer, I am interested in using my writing as a tool for disrupting and investigating existing narratives as a way to question their inherent power structures and expose alternative marginalized voices. As an artist, I use handmade books, papermaking, letterpress printing, and digital projects to build platforms and homes for these narratives. As the Founding Director of this Center for Writing, book Arts & Publishing, I provide opportunities to engage with books to advance the diversity of narratives in Caribbean literature. I think that we need to see ourselves take this action rather than outside forces.

“their political potential is in their smallness and how they empower people: tomorrow, anyone could found a new press to publish the work that needs publishing, and they could run it collaboratively in relation to community and readers and political values” (Plum 21)

What would you say are the main challenges you’ve faced since starting this venture? On the other side, what benefits or advantages have you come across?

My main challenge right now is funding and manpower and the constantly fatigue of “clearing bush” since I am doing something different in The Bahamas. I pretty much exclusively run the space—I’m not just Founding Director and an instructor in the workshops but Studio Manager, Communications & Marketing, Admin & Accounting, etc. I’m not sure I’m doing anything particularly well and I often feel like I’m yelling into the void, and my own practice is on the backburner. I’m trying different initiatives to see if they work and often I fail a lot or feel invisible or devalued, sometimes even by folks in my community and especially by our government. I’m trying to figure out if I should go non-profit and always on the look-out for funding which is very hard to come by, so the admin is staggering and the constant bureaucracy and dis-ease of doing business here wears me down often.

“The constant concerns of all of the interviewed small presses were survival and funding” (Bold 95)

So my main challenge is also believing in myself and in this power of this space to transform our literary and visual art landscape in the face of a lot of rejection or people not really understanding what it is that I do. On the flip side, I feel really fortunate to have the opportunity to run this space that has supported so many people already. I’ve met some creative folks who are so talented and who just “get it”, get what I am doing, and that is so exciting to me, to collaborate with them and support them in order to make this kind of craft visible in our part of the world. I also find it advantageous not to be aligned with or supported by any other entity—not the government, not a hotel, not investors or a board with their own agendas. And that means I can do what I want—it means real “freedom of the press”. That comes with great responsibility of course, so I often create and support programming and work that is progressive, subversive, intellectual, and humanistic. Which often feels at odds with our society/Bahamian values. I’m grateful I can make this a creative, collaborative, and inclusive space that values all expressions, experiences and stories.

“Reflecting on her engagement with the small press, Kruchkow stressed the small press publishing community’ s commitments “not only to literature but also to social and political movements”” (Kaja 44)

Is there anything else you’d like to say about the press or the industry or even yourself?

In 2024 I’m hoping to offer writing residencies, a self-publishing residency, and begin publishing books again as I’ve been focusing for many years on other projects and programming through the press.

so what now?

Johnny Parker II has self-published a lot of his own work but even he chose to publish one of his books through a small press instead of on his own. Even if you can do it, sometimes you don’t want to.

“Working with a publisher, it’s almost like a relief in a lot of ways because, all of sudden, it’s like a relief in a lot of ways” (Gagnon 74)

“With a publisher to handle “printing, the cost of paper, things like that,” he says, “I can just focus on telling the story”” (Gagnon 74)

I read Sonia’s words and I’m inspired because it’s everything I’ve been hearing about since this idea lodged itself in my head all those years ago. Community, opportunity, passion. The idea of not waiting on somebody to come and do something for you if it’s something you really want to do.

We’re in a time of change!

“The real game changer — which makes it easier to go to a small press — is social media” (Rich 64)

We shouldn’t have to wait on others to tell us what we can do or if we can do it. Who’s to say I’m not doing it now? In this digital age, would it be a crazy idea to question whether this website is infact my own digital micro press? I’m creating the stories, thinking about their presentation in form, and currating a view for the public. I even intend to “distribute” the links among other social media websites.

Not to say I’m doing anything close to running a press! No waaay. A website or blog is something that differs too greatly in form and content from a book. I’m just a gyal with a site doing TINGS!

“Blogs are thus more dynamic than older-style home pages, more permanent than posts to a net discussion list. They are more private and personal than traditional journalism, more public than diaries” (Jenkins 176)

But this is something adjacent to it for sure. An opportunity provided by the internet and the possibilities digital media provides. Something to question as the world moves forward. Remember when ebooks weren’t real books? And now they’re saying audiobooks don’t count as reading. I bet they said small presses don’t count when they first started popping up. I bet they still do. But all these forms of media and the ways they’re published matters!

Works Cited

Bold, Melanie. “An ‘Accidental Profession’: Small Press Publishing in the Pacific Northwest.” Publishing Research Quarterly, vol. 32, no. 2, June 2016, pp. 84–102. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12109-016-9452-9.

Gagnon, Milan. “‘I Can Just Focus on Telling the Story’: A Self-Published Author Finds Support with a Small Press.(Johnny Parker II).” Publishers Weekly, vol. 269, no. 40, Sept. 2022, pp. 73-5. EBSCOhost, https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edscpi&AN=edscpi.A721347800&site=eds-live&scope=site&custid=s5672116&authtype=sso.

Jenkins, Henry. Fans, Bloggers, and Gamers : Exploring Participatory Culture, New York University Press, 2006. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/okanagan-ebooks/detail.action?docID=865571.

Marczewska, Kaja. “The Small Press at the Library.” Chicago Review, vol. 66, no. 3–4, Jan. 2023, pp. 33-46. EBSCOhost, https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsltf&AN=edsltf.A765969991&site=eds-live&scope=site&custid=s5672116&authtype=sso.

Martire, Jodie Lea. “Amplifying Silenced Voices Through Micro- and Small-Press Publishing.” Publishing Research Quarterly, vol. 37, no. 2, June 2021, pp. 213-26. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12109-021-09797-7.

Plum, Hilary, and Matvei Yankelevich. “Small Press Economies: A Dialogue.” Chicago Review, vol. 66, no. 3–4, Jan. 2023, pp. 10-22. EBSCOhost, https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsltf&AN=edsltf.A765969989&site=eds-live&scope=site&custid=s5672116&authtype=sso.

Rich, Ronda. “Different Projects, Different Paths: A Veteran Author Recounts Her Experiences Working with Big Houses, a Small Press, and Self-Publishing.(Soap Box).” Publishers Weekly, vol. 270, no. 29, July 2023, p. 64. EBSCOhost, https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edscpi&AN=edscpi.A759054761&site=eds-live&scope=site&custid=s5672116&authtype=sso.

Sharpe, Martha. “KEEP CALM, CARRY ON: The Owner of a Canadian Bookstore and Small Press Says That, in Spite of Challenges, Bookselling and Publishing Can Still Thrive.” Publishers Weekly, vol. 270, no. 42, Oct. 2023, p. 28. EBSCOhost, https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edscpi&AN=edscpi.A771914010&site=eds-live&scope=site&custid=s5672116&authtype=sso.

Got anything to say?